Could you enlighten us about the main historical waves of Sudanese migrations towards Europe? What are the particularities of the Sudanese migrants in Europe, and how do their profiles differ from individuals who migrated to Gulf states?

Alice Franck: We can say that there is an older Sudanese immigration in Europe, composed more or less of people belonging to the elite, who were heading primarily toward England. The political refugees who appeared in France from the 1990s1 in connection with Omar al-Bashir’s coup d’état were few. The entire Sudanese population in France, accounted for in 1990, represented apparently less than 1,000 people. In the 1990s, the Sudanese population in France was constituted by the staff of the Sudanese embassy, political refugees – who were rather communist – and immigrants who came for economic reasons.

Since 2005, in connection with the Darfur crisis, Sudanese migrations to France have become more important and have increased in recent years, especially since 2010. For two years – in 2015 and 2016 – the Sudanese have been the primary nationality seeking asylum in France.2 Asylum is indeed the main administrative and legal solution for young men from Darfur and other surrounding regions in conflict, in order to stabilize their presence in France, due to increasingly restrictive national and European migration policies.

The increasing number of Sudanese immigrants we have seen in recent years in France is, of course, related to the conflict in Darfur, but this can also be linked to the legal frameworks of asylum policies which are mainly directed toward people from regions recognized as being in crisis by international and local migration authorities. Again, we find a distinction between newcomers and an older, more educated Sudanese diaspora from wealthier classes in Sudan. Sudanese migrants generally head toward the route to England via Calais, but that pathway is increasingly difficult.

In England, where the Sudanese population was already important, it has also considerably increased in recent years, growing from 10,000 people recorded in 2000 to almost 20,000 in 2015.3 Asylum claims are however lower than in France: at around 1,500 in 2014 and 2016, compared to approximately 3,000 and 9,000 for France at the same dates4, providing evidence of the differences in terms of statistical categorizations and welcoming policies.

In comparison, immigration to the Gulf states is more remarkable and representative of Sudanese migration practices: while in 2015 Europe welcomed around 45,000 Sudanese, in the same year, 600,000 lived in Gulf states, especially in Saudi Arabia. This older immigration is important as of the 1970s, when development policies, and especially those in agriculture, failed when they were supposed to transform Sudan into the breadbasket of the Arab world. It is an economic immigration, ruled by a system of private sponsors (kafala) supported by the Gulf regimes. In Khartoum, in the 1970s and 1980s, villa districts arose from Sudanese monetary transfers, coming from the Gulf states, bearing names which are suggestive of this migratory process: Ryad, Taef, Al Mamoura.

Given the current economic context in Sudan, and despite stronger policies on family reunion and against illegal immigration, the Gulf states still remain a major employment opportunity for the Sudanese. If the Sudanese population in those countries seems less politicized than in Europe, it can be explained by less political public areas for expression and different legitimation and negotiation mechanisms of one’s place within the host society. This is more political in Europe, while it is rather based on economics in the Gulf. When trying to follow the current uprising on social networks, the rare images that arise from the Gulf states are substantially individual actions or stem from small groups – filming themselves and / or taking one’s picture with a Sudanese flag to support the demonstrations in the country for example – than organizing an event which attempts to make the uprising visible outside its borders.

Last week, a Sudanese friend residing in Riyadh confirmed the absence of Sudanese mobilization in Saudi Arabia, because it is impossible to assert political claims from the Saudi Arabian public areas. It is therefore likely that Sudanese activists do not primarily move to the Gulf states where their actions are limited. Thus, the resistance acts take various forms. For example, we have seen Sudanese artists and activists, who are residents of Saudi Arabia, launching a call to continue the protests, and we can also mention the women’s music group Salute Yal Bannot, who took the opportunity during a concert in Kuwait to talk about the situation in Sudan.

When did the Sudanese diaspora begin to mobilize?

We can say that the mobilization of the Sudanese diaspora was really very rapid, especially in France. The current revolutionary movement started with the demonstrations in Atbara on December 19th, and as soon as December 23rd and 24th, there was a mobilization of Sudanese migrants in Paris in front of the Sudanese embassy. In the rest of France, we observed the same tendency: in Lyon and Marseille, for instance, on December 29th there were also demonstrations gathering around a hundred people.

“This strong mobilization from abroad is in contrast to the lack of attention given to the Sudanese uprisings by mainstream Western media.”

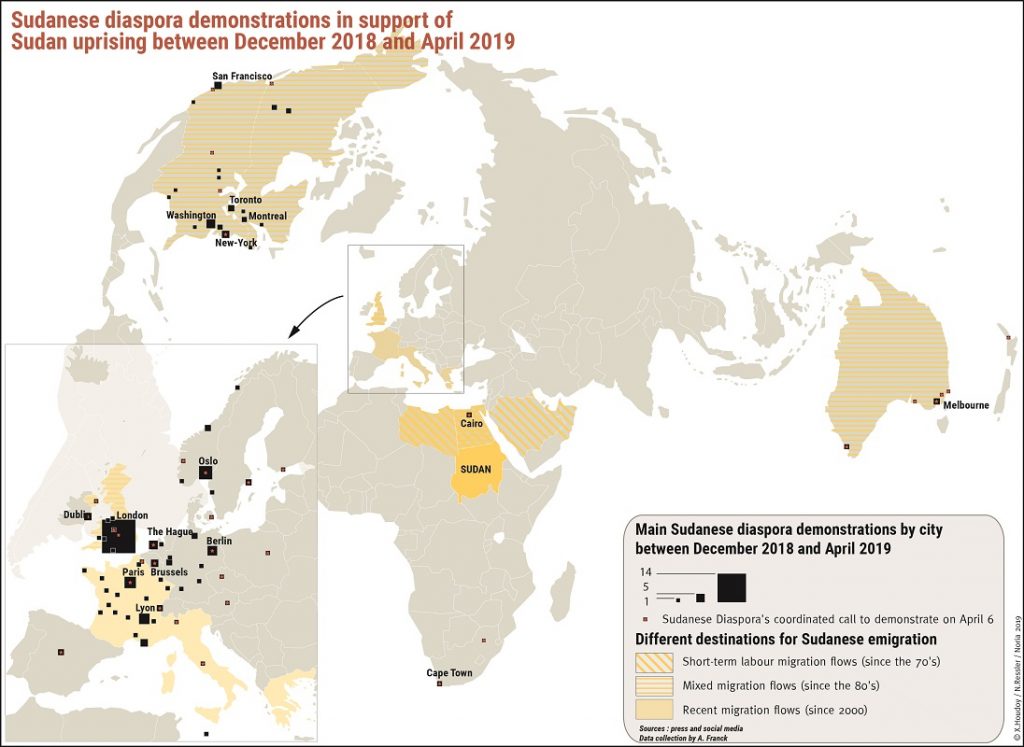

However, this is not peculiar to France, or to Europe, since on December 24th Sudanese in The Hague and Washington were also mobilizing in large numbers. Starting at Christmas the mobilization of the Sudanese diaspora grew, organized itself, unified hundreds of people and began to be relayed on social networks. Until then, only spontaneous gatherings with a few dozen people had broken out, particularly in front of the Sudanese embassies in countries where the Sudanese were established: in Calgary and Edmonton, Canada, in Victoria and Melbourne, Australia, in Dallas, Houston, and Iowa in the United States, in Dublin, Ireland, in London and Manchester, England, but also in Cairo, where the desire to gather in front of the embassy was quickly undermined by Egyptian authorities. This quick reaction proved to be resilient since the Sudanese diaspora continues its mobilizations. This strong mobilization from abroad is in contrast to the lack of attention given to the Sudanese uprisings by mainstream Western media in these same countries.

Are the levers of political action different according to the exiled generation to which these people belong to?

I am precisely trying to list all the public events taking place in the world that support the demonstrations in Sudan and I am confronted by a first difficulty, which is my connection, as a French researcher, to specific channels of information. Does the large number of events that I cataloged in France (around thirty since December 23th, opposed to 22 in the United States) come from a better connection on my behalf to the Sudanese diaspora in France, or, of a more important media campaign in France, or of a difference in the methods of action which would explain why some of them escape my reach? A little of both it seems to me.

Apart from the number of organized events, we can already notice from this map some important information: the mobilization of the different Sudanese communities in the world is more or less centralized according to the country. If we take the case of England, out of 19 public demonstrations that were identified, 13 took place in the , mainly in Trafalgar square. This is a big difference with what is happening in France, where all major cities have seen Sudanese mobilizations (Paris, Lyon, Marseille) but also medium-sized cities like Dijon, Arras or Poitiers. This phenomenon reflects not only the impact of dispersal policies concerning recent immigrants arriving on French soil, but also the actions taken to reduce the number of immigrants in Paris by dispersing them throughout the country. To a lesser extent, we can also find this phenomenon in Germany. The Sudanese diaspora in Norway is also particularly active.

The phenomenon of concentration of supportive events in England, for example, also reflects the different Sudanese communities’ capacity to structure themselves and organize large-scale gatherings in symbolic places. Thus the success of the February 16th march in Washington, where more than a thousand people apparently assembled, had a strong impact on the Sudanese population. Buses were chartered from different parts of the country, which testifies to the material and financial means of supporting the movement within the Sudano-American community.

In Europe, this same eagerness to gather was expressed by demonstrations, organized on March 2nd in Brussels before the European Union and on March 22nd in Geneva in front of the United Nations Office. They have had gatherings of people beyond national borders. On April 6th, the anniversary of the fall of Nimeyri in 1985 following a pacifist revolution, a call to protest simultaneously throughout the world was launched by ASASU (Association of Sudanese Abroad in Support Uprising in Sudan), and this mobilization has often been repeated among the Sudanese diaspora.

In addition, not only demonstrations and sit-ins are organized, but many different methods of action are emerging in Sudan and outside of Sudan since the beginning of the uprising. Press conferences, approaching political parties (Socialist Party in England, young communists in Lyon, etc.), and certain governments (in the United States in particular), scientific events, concerts, and varied events which offer information on the context, activism, and expression of solidarity are organized in order to make visible and mediatize an uprising that has been struggling for four months to meet the interest of classical media and Western diplomacy.

Translators found a role to play in broadcasting information about the protest movement. A group was created on social networks: “Sudanese Translators for Change.” Since January 6th, 2019, it relays and shares the latest information on Facebook on the uprising in Sudan by translating them initially to English and today also to French, German, Greek, Spanish and Romanian. This network, which has grown quickly (they began with three members and are now forty), connects Sudanese based not only Europe and America, but also in the Gulf states and is a good illustration of support from worldwide diaspora activists.

“Funds can also be raised to organize supportive events, funding performances, and surely also to support the movement in Sudan.”

Always in the perspective of making the uprising in Sudan visible, groups organize artistic performances, which then circulate on social networks. This is the case in France with the ASUAD group (Activist Sudanese United Against Dictatorship). A silkscreen printed poster representing Sudan in struggle has recently been launched for sale in order to support future actions and is posted in some major French cities.5 There is a true artistic mobilization and it is aimed at people outside of Sudan as well as towards the Sudanese in Sudan. There are many songs and poems, often in Arabic and especially emanating from the diaspora, explaining how helpless they feel not to be in Sudan and showing their support for the protesters. We also see videos circulating, caricatures, and drawings. They are made for people in Sudan, so the texts are in Arabic, sometimes with English subtitles to show what’s happening.6

At the same time, some kitty and money pots have been organized for support, which seems to have a positive response from the Sudanese community abroad. For example, in some cities where meetings take place to talk about the uprising, they also sell cakes, concerts are organized to raise money for the martyrs of the revolution and their families: all this counts too! Funds can also be raised to organize supportive events (activists traveling to Brussels, Washington, etc.), funding performances (group ASUAD), and surely also to support the movement in Sudan.

Are there also mobilizations that can be described more as “institutional” and would attempt to structure the movement? Who are the leaders of these remote political mobilizations in Europe? Can we see a particular profile of a leader emerge?

I think it is important to underline that there has been a strong momentum within the Sudanese diaspora, which, for the time being, has gone well beyond the usual political, regional and ethnic divisions. In France, young men who arrived in the last years were more mobilized on the Darfur issue and hosting conditions in France. The demonstrations to support the movement nevertheless brought together all the Sudanese, including the older generation of immigrants. There is, therefore, a gathering of forces of people from Darfur as well as those in the north and center of the country who are also activists, recently or less recently settled in France.

The phenomenon must be analyzed as a mirror of inclusive slogans such as “We are all Darfur” which appeared in Sudan in response to the regime’s attempts to exacerbate regional and ethnic tensions. The primary objective of the Sudanese movement, which is to bring down the regime, creates a consensus within the diaspora. The Sudanese in France testify that political discussions are now easier and transcend old divisions of class, ethnicity, etc.

In spite of everything, if we continue to observe the situation in France, which is better known to me, the support of the movement evolves over time, especially on the micro-local scale in Paris, where more people are mobilized. The demonstrations still largely gather the entire Sudanese population, but a myriad of events are developing at the same time, and these are carried out sometimes by one group of Sudanese in exile – for example, young Darfuris recently arrived – or another group, like the old exiled community.

So, in a way, the different generations in exile play a role, but it’s not the only factor that configures support groups. There are, for example, groups that are structured around political affiliations: the rebel movement of Abdel Wahid el Nour, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), and so on. Other groups are shaped around age or gender criteria: “Sudanese Youth Initiative in France”, or “Mahan min ajl Al tahir” which is a women’s group.

Furthermore, known activist personalities integrate support groups when they arrive in France without regard to their arrival date. The militants’ political trajectory does not stop with immigration and the leading figures of the protest in Sudan benefit from their militant capital here within the Sudanese community.

Contrary to what one might think, the diversity of existing activist groups or associations is not an indicator of divisions within the Sudanese community in France. Many members of the Sudanese community are part of numerous different structures, whether these are made for militant or socio-cultural purposes. However, this Sudanese community should not be considered as entirely homogeneous, and of course, internal dissensions exist, especially regarding the place of Islam within the protest movement, and the ways of conceiving a future Sudan.

Each group or activist uses its/his or her networks and connections to display the Sudanese situation: many Sudanese activists are connected to the French association network which deals with hosting conditions in France and the question of the refugees; this bears testimony of the resonance between different militant networks – French and Sudanese in this case. It is also by means of this support that certain events are held, and that information circulates throughout France. The booklet published in 2016 by the publishing house Maison de la grève de Rennes “From Calais to Sudan: 3 days with the Sudanese Rebels” is found alongside the new brochure published for an evening event by the “Friends of Lyon” [Amicale de Lyon] entitled “Sudan: What Revolution in Exile?” (On March 24th, 2019). The support of the Sudanese uprising makes the continuity of the political trajectories of some Sudanese militants particularly visible, and these become local leaders of the movement in their host city.

What is the connection between the groups mobilized in Khartoum, for example, the Association of professionals, and the diaspora activists?

We have already mentioned the diaspora’s various methods of action, and we must probably insist on the flow of information, videos, ideas, via social networks (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) that currently occupy a central place in the connection between here and there as well as in the constitution of the image of a Sudanese people united behind the same struggle, even at the risk of amplifying this reality.

“The calls included the diaspora during the days of mobilizations, either at the same time as actions were carried out in Sudan or, on the contrary, so that something happened in the world almost every day.”

The Sudanese Professional Association (SPA) publishes calls for mobilization on social networks that go beyond the national framework and confer a role to the diaspora. Therefore, the leaders of the movement call for protests in front of Sudanese embassies abroad and in front of the host countries’ foreign ministries.

It is also interesting to mention that the inclusion of the Sudanese diaspora appeared at the precise moment when the association was being built and began to formalize its calls: the meeting places became more precise, the planned and alternative routes of demonstrations were detailed on maps, manifestations based on themes gradually appeared (women’s march, march of martyrs, etc.), calls coordinating actions over a week were published. And these calls included the diaspora during the days of mobilizations, either at the same time as actions were carried out in Sudan or, on the contrary, so that something happened in the world almost every day. I think this is the first time a Sudanese political movement crossed national borders with such strength and such willingness to make the cause visible.

It also highlights the physical connections between the SPA and diaspora activists. In France, there are few representatives of the association, but if we look at England, the mobilization is settled as a mirror of what is happening in Sudan, partly carried out by the professional association of doctors (Sudan Doctor Syndicate UK / Ireland) which brings together Sudanese doctors in England and Ireland. In the United States, professional associations also play a role in the mobilization. The politicized opposition groups are also more numerous and better represented, which explains the greater presence of SPA members in these countries.

Moreover, the flow of activists for four months and the beginning of the uprising have not ceased and it is likely that the SPA networks, as well as the family networks, are organized to get people who are particularly targeted by the repression in Sudan out of the country when they can. We can think that there are currently activists arriving in European countries and imagine that others will take over in Sudan. Four months of revolt is long, and for the moment there is no demobilization or loss of impetus, neither in the diaspora nor in Sudan.

Notes

- Ester Serra Mingot, Protecting across borders. Sudanese families across the Netherlands, the UK, and Sudan, 2018, Ph.D. in Geography, University of Maastricht and University of Aix-Marseille, p. 69. ↩︎

- See the claims for asylum in 2015 on the website of the Department of Immigration, asylum, reception, and support of foreigners in France of the French Interior Ministry. ↩︎

- For a little more than 2500 accounted for in France (Serra Mingot, op.cit). ↩︎

- For a little more than 2500 accounted for in France (Serra Mingot, op.cit). ↩︎

- The silkscreen sold online from the artist’s website. ↩︎

- Elhassan Sara, “How Sudanese Art is Fueling the Revolution”, Okay Africa, February 21,t 2019. As the articles show: Le Monde, AFP, “Le caricaturiste Khalid Albaih, « ambassadeur » du Soudan révolté”, April 3, 2019, and, Av Israa Elkogali Häggström, « Art for the Revolution: How Artists Have Changed the Protests in Sudan », Kultwatch, April 2, 2019. ↩︎