On October 2nd, 2016, the Colombian people voted “No” in the referendum to ratify the peace agreement between the State and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC, created in 1964), which had been signed in an atmosphere of great optimism on the 26th September in Cartagena. In spite of widespread enthusiasm among political actors, the backing of the international community, the support of left opposition parties and the Pope’s appeal for peace, 50.23% of voters (a margin of barely 60,000 votes) rejected the agreement reached in Havana after four years of negotiations. The former president, Alvaro Uribe, publicly supported the “No” campaign through multiple media appearances. Yet those Colombians who voted “No” are difficult to identify. Who are they? Was it peace they rejected?

A new agreement was announced on November 12th, responding to some of the demands of those who opposed the first agreement. They are yet to approve the new text, which both government and FARC representatives claim to be definitive. Although two guerrillas were killed by members of the armed forces on November 14th in unclear circumstances, the ceasefire remains in force, but a continuing stalemate would risk weakening it.

The peace agreement, negotiated in Cuba by the government and the FARC over a period of four years, was almost immediately put to a referendum on October 2nd, in accordance with the wishes of President Santos. However, the Colombian people said “No” to the peace deal that was supposed to put an end to half a century of conflict. How should this vote be interpreted?

Jacobo Grajales: As far as interpreting the referendum result goes, I think that firstly it constitutes a manifestation of a certain discrepancy between what was negotiated in Havana and what the Colombian people perceive as their priorities. Very clearly, “No” voters criticised a government that concluded a peace deal in isolation, a peace deal which was denounced on several counts, notably because of the pardon granted to FARC guerrillas. Politicians who campaigned against the peace agreement were in this respect capitalising on the rancour and resentment of a section of the Colombian population towards the armed insurgents. The peace deal was also denounced as being politically dangerous, because it pushed for the FARC’s participation in the political process. The opposition propagated lies, telling people that the FARC’s involvement in politics could eventually lead to the establishment of a socialist model à la Chavez. It was a very dirty, dishonest campaign. I also believe that the result is a symptom of a lack of political commitment, both from the government and the FARC, to defend the peace agreement in the eyes of the population. The agreement was unveiled very shortly before the referendum, without any political education and without mobilising the Colombian people to defend it, because the government believed it was a done deal. It is moreover very telling that the signature of the agreement took place before it was presented to the electorate.

However, focusing solely on this analysis does not even begin to tell the whole story. In order to understand how people voted and what their message was, it is necessary to study the geography of votes, and analyse the different strategies of the “No” campaign. If we begin to examine how people voted on the basis of municipality-level data, several elements stand out. One analysis that emerged in the aftermath of the referendum stated that direct victims of civil war voted “Yes”, while those who watched the war on television voted “No”. This explanation is a little simplistic and really needs to be nuanced. There are indeed areas that have been hit hard by the war, and in which the population voted in favour of the peace agreement, but this vote does not necessarily denote a mobilisation of victims. Many of these areas are located in peripheral regions, and the more nuanced analyses currently available highlight the fact that the inhabitants mobilised above all for an increased presence of the State, such as more investment in public services and infrastructure. I think that part of the “Yes” vote expresses this desire for a redeployment of State presence, which would have accompanied the implementation of the peace agreement.1

The “No” vote is also highly composite. One of the examples that struck me in territory-related analyses is the fact that, in some of the working class districts of Bogota, there was a majority of “No” voters. When journalists conducted investigations there, people told them that they voted against the agreement because they feared that the allowances that were to be given to the guerrillas would detract from their own welfare benefits. In other words, the welfare policy for demobilised guerrillas was perceived as designed at the expense of welfare benefits for working class neighbourhoods. The third element of this analysis is that, in fairly plain terms, the failure of the referendum can be explained above all by the capacity of the “No” campaign to mobilise the electorate. Concretely, this means that they succeeded in mobilising political networks, including those that supported Zuluaga (the candidate of the Democratic Centre party, who was backed by former president Alvaro Uribe and is an opponent to current president Juan Manuel Santos), the Uribiste candidate in the last presidential election (of 2014). When these two separate voting maps are superimposed, they match nicely.

In addition, a certain number of actors mobilised for related reasons: most evangelical churches, for instance, mobilised their followers against the peace deal in order to defend a certain model of society. Against a backdrop of tensions surrounding the role of the traditional family, this agreement was cast as a vehicle for the famous “gender theory” some reactionary movements are currently denouncing.2 Similar reasons explain the silence of the Catholic Church, which refused to defend the agreement. Behind all of this, there is nonetheless a degree of successful political mobilisation, well-established communication techniques, and a campaign that drew on absolutely all available means and succeeded in articulating several political, economic, and societal rifts. What I mean by that is that people, as is the case in any referendum, did not simply respond to the question they were asked. The result of the vote is above all the upshot of the successful strategy of the “No” campaign.

Since these rifts were mobilised so easily and so rapidly, is it fair to contend that Colombian society is still polarised? On the one hand large towns and cities that benefit from economic growth, on the other poor rural areas that are more affected by violence? Or maybe polarised between conservative elites and supporters of an alternative form of development?

Yes, the interesting thing is that there was an alignment of several rifts, even though this notion is extremely simplified and remains a mere hypothesis. On one side you have the supporters of the peace agreement, who are in favour of broader political participation – not just including the FARC, but also working class people –, who with this agreement may well have found new spaces and means of expression and an impetus to revitalise direct democracy, notably at the local level. You also have people in favour of a “pluralistic” economic model, in which small economic actors, better protected and supported by the State, could find a new role alongside large-scale manufacturing, agro-industry, and the mining industry. I am particularly referring to family agriculture. On the other side, you have a group of sectors that are concerned about these developments that may damage the dominant economic model, even though such developments were in reality very tenuous, because there were no guarantees in that respect in the peace agreement. We can also identify, and I think this point is very important, sectors that feel threatened by the transitional justice system provided for by the peace deal, whose procedures would undoubtedly have promoted free speech and unleashed an enormous tide of information. While the conflict in Colombia is unquestionably better documented than other comparable wars, thanks to the work of the judiciary and the activity of a wide array of human rights activists and organisations, this would have helped put faces on individual and collective responsibility, as well as identify the financial backers of armed groups and the role played by different economic groups, major corporations, etc. These measures would have facilitated a kind of historic uncovering, and were thus considered dangerous by the interest groups gathered around former president Uribe (2002-2010) and the conservative party, which played an important role in the “No” campaign.

The power of the conservatives in Colombia seems to have surprised “Yes” supporters. Given that you have worked on armed and particularly paramilitary actors, do you think the latter played a political role during the referendum campaign?

I have not seen anything suggesting they tried to prevent people from mobilising. Although some messages circulated, including pamphlets calling for people to abstain and threatening those that voted, the influence of the paramilitary groups that have succeeded those of the 2000s is a far cry from that of their predecessors. These groups more often limit themselves to the defence of their economic interests and play a much less pronounced role in mobilising the population or in shaping is political behaviour. So in this respect it is not surprising that they were not central actors. However, the geography of the vote underlines the fact that the traditional areas of activity of the paramilitary movement, such as the northeast of Antioquia, certain parts of the Caribbean coast and areas further inland, predominantly voted against the peace agreement. Here I think we can identify an electoral sociology that corresponds to a conservative vision of society, and to a revanchist discourse against the insurgents. Nevertheless, in these same areas where the paramilitary movement was strong, notably the Caribbean Colombian coast, popular mobilisation was also strong. Here the map of the “Yes” vote almost perfectly corresponds to the map of rural and trade union mobilisations since the 1970s and 1980s. It is one area in which the social fabric has not always survived paramilitary violence but which still retains a tradition of social struggle.

The ceasefire between the FARC and the government forces has been extended to December 31st, 2016. Since the referendum, numerous civic demonstrations in favour of peace have taken place and certain political leaders from the Colombian right have reaffirmed their desire for peace. What are your predictions regarding the fate of the peace agreement after the referendum?

A new text was announced on November 12th, which should be formally signed on November 24th. It responds to a certain number of objections from “No” voters, while maintaining the essential elements of the previous text. Former president and current senator Alvaro Uribe has come out against this text, and has vowed to fight “in parliament and in the streets” to block its implementation. The ratification of this new text by congress should be done relatively swiftly, and it is unlikely that the opposition will be able to obstruct its progress given that the coalition in favour of the agreement currently dominates the parliament. In the medium term, this could weaken the implementation of the peace deal, notably because “No” supporters could denounce a “denial of democracy”, and this could form the basis of a lasting polarisation on this issue, particularly concerning the 2018 presidential election.

During this period, the strategy of the actors that helped shape the first deal was marked by a feeling of urgency. The FARC took a very positive stance, stating that they did not envision their future as anything else than a political movement. Nevertheless, an armed movement which has not yet been demobilised, and instead finds itself a ceasefire without any prospects for its combatants, constitutes an extremely dangerous situation. The urgent task for the government over the past few weeks has thus been to accelerate the implementation of demobilisation and disarmament measures. Without the signing of the new agreement, the risks of dissidence or of a clash with the army could have catastrophic consequences.

The government then attempted a kind of win-win solution by opening negotiations with the ELN [Ejército de Liberación Nacional/National Liberation Army, another guerrilla group]. This might allow them to respond to one of the arguments of the opposition, which states that the present agreement would not in any case lead to peace, given the existence of other groups, and because the ELN would simply take up the FARC’s positions. The negotiations with the ELN would thus help to frame this peace deal as a kind of “grand national pact”. But the ELN is a very different kind of group from the FARC. This guerrilla movement has complex demands and seeks an extremely broad level of social participation in the negotiations, a kind of grand social forum, with no agreements concluded abroad. However, it is hard to see how such an initiative could rapidly be a success, and time is not on the side of the negotiations. All the work that has focused on the ELN demonstrates that this organisation is even more fragmented than the FARC, which a much looser hierarchy. It took more than four years to negotiate with the FARC, which is a highly centralised movement. In concrete terms, I do not know how things could proceed more quickly with the ELN. And in the midst of all this there have been significant social demonstrations since October 2nd, calling for the peace agreement to be maintained, for the ceasefire to be observed, and for the peace deal to be rapidly renegotiated. These demonstrations are significant because they put pressure on the government and create a favourable environment for peace. The ELN has been put under a great deal of pressure by some left-wing movements in Colombia they are close to. These movements are urging the guerrilla group to sit down at the negotiating table. This shows the strength of certain civilian movements, which play a role in non-armed politics and which can exert some degree of influence on the course of events.

But in my opinion the major unknown factor – and I really don’t have any answer on that –remains the strategy of the supporters of the “No” campaign, and chiefly of Alvaro Uribe. In one sense, their victory took them a little by surprise, and it is highly likely that they did not have a plan in mind should their mobilisation prove successful. Now they find themselves in this situation, which is extremely complex to manage. They do not know how to appear as a constructive force in such a way to be able to capitalise on their victory while negotiating a high price for their support, which would be the strategy of a rational actor.

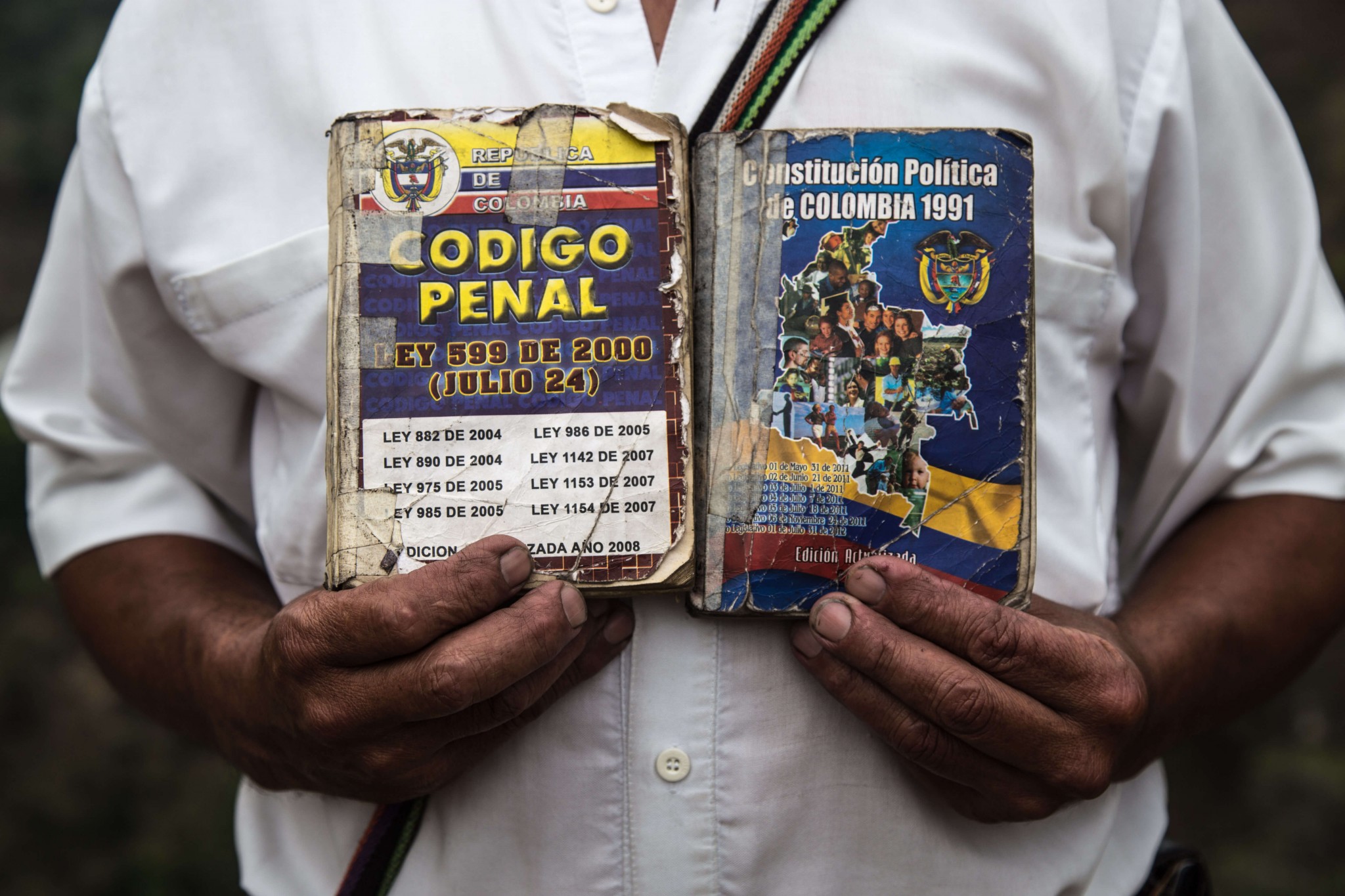

The pictures that illustrate this article were taken by Tomas Ayuso. To see the full photo report, click here.

Notes

- The agreement provided for public investment in infrastructure and improved access to public services (notably healthcare and education) for inhabitants of the countryside. This State presence could also be promoted by the creation of a rural land registry and by the plan to formalise 7 million ha of small and medium plot land that was included in the agreement. Finally, several provisions of the peace agreement implied new dialogue between the State and the marginalised areas of the country, notably by providing for a greater level of exchange in the realisation of territorial development plans. ↩︎

- Certain “no” supporters have stated that the peace deal calls into question the traditional concept of the family (comprised of a man and a woman). The final agreement makes no mention of this debate, but each point of the negotiations attempted to include a gender-based approach. From the beginning of the peace talks, several women’s and LGBT associations campaigned for the rights to be taken into account. The final agreement partly includes their participation, for instance through the possibility for female heads of the family to obtain property titles (which were previously exclusively in their husband’s name) or the consideration of rape and sexual favours as crimes not subject to amnesty. ↩︎