Syrian and Iraqi borders dynamics exemplify the ongoing metamorphoses in the Middle East, and their neighbors in the region—Turkey, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon and Israel—deeply feel the consequences of the waning of the two political regimes. Therefore, our analysis aims at identifying the role that these multiple borders, built by security-obsessed authoritarian governments actually play when the latter are unable to extend their rule over their own territory. Therefore, the following question arises: what types of actors manage to appropriate the limits of a splitting-up territory, within which certain regions are likely to become the scenes of crucial territorial reconstruction processes? [mfn] Julien Thorez (2011) notes that ‘‘the multiplication of actors modifies the social dynamics and the mechanisms of production of space’’ in the case of newly established post-Soviet borders of Central Asia.[/mfn]

In times of conflict, borders are margins that are even more difficult to control. They sometimes become areas moved by specific dynamics, where local and regional actors interact. Groups that seek to ensure military and/or economic control may become critical players in the ongoing transformations of the region. Here, “transformation” does not mean a simple change of tracks but a radical mutation in the way that borders and various circulation flows are controlled.

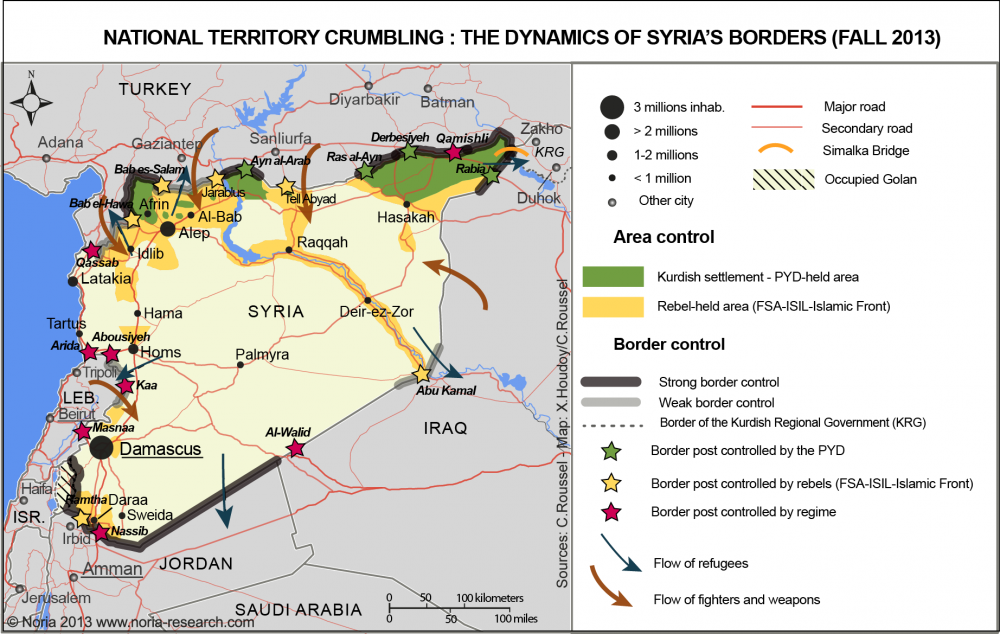

The following lines are aimed at introducing the changes taking place in the border areas of Syria and Iraq, whether between the two countries themselves or between their neighbors.

Support for the Syrian rebellion (from Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan) involves the circulation of men, money and military equipment to the front. These countries not only host military training camps for Syrian rebels, but also logistical centers (military command centers, fundraising offices, etc.). Moreover, Jordanian security services let Syrian activists and Free Syrian Army members (FSA) re-enter Syria through the Daraa’s province border, even though it is closed to refugees. They are the only people allowed to travel between the two countries. Without such a support base in Daraa, and without access to logistical support through Jordan, the rebellion in the southern part of Syria would certainly be defeated.

On the opposite way, Turkey, Jordan, Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan limit the influx of refugees by closing their borders for a given period of time through strong military measures. This practice, although rarely recognized officially, aims at containing the heavy pressure that Syria imposes by using refugees as a political weapon – the presence of hundreds of thousands of Syrians in neighboring states is an enormous financial burden and constitutes an element of real destabilization[mfn]The pressure is on the labor market, the real estate market and more generally on the health and education infrastructure.[/mfn].

Strict control of the border has then permitted Jordan to select asylum seekers: for instance, Syrians of Palestinian descent are not allowed in the Kingdom[mfn]Jordan estimates that contrary to the Syrians, the Palestinian refugees would settle in her territories for an indefinite period if any opportunity was given to them and they would never want to return to Syria.[/mfn]. Moreover, since spring of 2013, the Jordanian border between the Israeli-occupied Golan and the margins of the Druze province of As-Suwayda has been closed to all refugees[mfn]Numerous points of clandestine border crossing between the province of Daraa and Jordan were closed-down by the Jordanians. The only point of crossing remaining open for the refugees to get into Jordan is located East of Jabal Al-Druze in the desert near the Iraqi border. The Syrian refugees reach Jordan through that passage. Yet the current flow is comparatively lesser than that of the winter of 2012-2013, given the fact that it is a costly journey with significant difficulties.[/mfn], although Syrian rebels control almost all the regions neighboring Jordan. On the other hand, regime-controlled As-Suwayda province allows Syrian troops to remain in this part of the Syrian-Jordanian border, to maintain large military bases next to the rebel-controlled province of Daraa, as well as to keep the Nasib/Jabir border station.

The case of Iraq is simpler. Concerned by the arrival of Syrian refugees, the government closed its border with Syria in August 2013. In the meantime, Iraqi Kurdistan sporadically allowed the entry of refugees. Yet, since September 2013, the entire border has been sealed.

Turkey, while facilitating the crossing of rebel fighters and jihadists into Syria, limits and controls the flow of Syrian refugees attempting to enter its territory[mfn]‘‘Turkey started to limit the entry of Syrian refugees into its territory except for the people with passports and the wounded’’ (Article from L’Express, May 25th, 2013).[/mfn]. Yet, the Turkish border cannot be compared the Jordanian one. First, the frontier is much longer, which makes it more difficult to monitor. Furthermore, territorial control is not as homogeneous on the Syrian side. Bashar al-Assad’s forces are still present in some areas (Kesab in the West and Qamishli in the East) but rebel groups – Islamic Front, FSA, ISIL[mfn] Islamic State in Iraq and Levant[/mfn], Al-Nusra Front – are fighting each other not just for the territorial domination in the northern province of Aleppo and Ar-Raqqah, but also for the control of various crossing points, vital for their supplies (Bab al-Hawa , to Azaz in Tell Abyad). As for the Kurds, some of which joined YPG[mfn]Yekineyen Parastina Gel – ‘‘People’s Protection Units’’, is the armed wing of the PYD, Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat, Democratic Union Party, which can be considered as the Syrian branch of the PKK.[/mfn] forces, they firmly hold the Kurdish-populated areas. Finally, the Turkish authorities have become more openly involved than their Jordanian counterparts in the Syrian conflict by supporting some groups at the expense of those they consider harmful to their interests. This results in a highly volatile Syrian-Turkish border depending on who is in control on the Syrian side. In general, customs remain open and borders are permeable for activists, rebel fighters and jihadists in order to weaken the Syrian regime (region of Hatay, Kilis and of Akçakale). However, they tend to be more hermetic in Kurdish areas, like between Nusaybin (Turkey) and Qamishli (Syria) where Ankara is currently erecting a wall of separation in order prevent smuggling and illegal infiltration, mainly because of the PKK domination on the Syrian part of the border.

Inability to control, laissez-faire and clandestine trafficking (Iraqi borders with Syria, Turkey and Iran; Syrian borders with Turkey and Jordan)

Coming from Iran towards Iraqi Kurdistan, political refugees, students and fighters of Kurdish political parties opposed to the Islamic Republic of Iran (Komalah[mfn] Komalah is a revolutionary party founded in 1969 in Tehran along a Maoist ideology. Its Marxist program allowed it to create the Iranian Communist Party in 1983.[/mfn], PDKI[mfn]The Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan is a secular social-democrat party opposing the Islamic Republic. The party was founded in 1945 in Mahabad before the Iraki PDK ; it is a member of the Socialist International. The popularity of Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou (assassinated in 1989 in Vienna) contributed to its international fame.[/mfn], PJAK[mfn] Partiya Jiyana Azad a Kurdistanê – Party for a Free Life in Kurdistan – is the PKK branch in Eastern Kurdistan (Iran)[/mfn]) cross illegally, using smugglers to reach the Kurdish autonomous region, fleeing a state they consider as an “oppressor”. The price of the journey varies according to the area of passage and the difficulty of the route taken. It usually costs several hundred dollars per person, since the risk of imprisonment or even execution by border guards is a real threat. In general, the more difficult the passage is, the higher the chances of success[mfn]The activists wanted by the Iranian authorities cannot risk passing too close to monitoring stations. Thus, smugglers drive through the mountains by often long but safe trails.[/mfn]. From Iraq to Iran, smuggling networks are very powerful and support hundreds of villages (Roussel, 2013).

Flows of refugees between Syria and its neighbors also amount to illegal circulation. Few Syrian refugees would go through an official border post, except at the very beginning of the conflict. Most refugees that crossed the border illegally did so to escape the border guards that could push them back or extort money from them. Three years after the beginning of the war, the regime in Damascus has failed to control significant segments of its borders: refugees are rushing to reach Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq. With time, some of these crossing passages have become real ‘‘posts’’ for illegal border crossing[mfn]For example there are three important illegal passage points between Syria and Jordan and the majority of the refugees crossed the border from those until the spring of 2013. The Syrian side was under the control of the FSA, and the Jordanian army was controlling the other side of the river Yarmouk in Jordan. These passages, illegal at the beginning, became true hubs and are gradually fitted to facilitate transit and registration.[/mfn], while others are used for a limited period of time and then abandoned. The best example of illegal border ‘‘posts’’, though very tightly controlled by the Kurdish security forces, is the Simalka Bridge. This is the only crossing point through the Tigris River between Iraqi Kurdistan and Syria. This bridge is not an official border post, but a well-recognized informal entry point. Many others exist between Iraqi Kurdistan, Turkey and Iran. The Simalka Bridge was built at the end of 2012 to allow passage between the Kurds of Iraq and Syria. However, it quickly became a political issue between the Kurdish parties of the region, as the article will demonstrate. During the summer of 2013, tens of thousands of Kurdish refugees from Syria used the bridge to flee their region. Rivalries[mfn]The Syrian Kurdistan has become the theater of rivalry between PKK and PDK since the summer of 2012. PKK supports PYD whereas PDK tries to impose its constituents, smaller Kurdish parties that are gathered under the umbrella of SKNC (Syrian Kurdish National Council). The initial agreement between the two sides (Erbil accords, summer of 2012) did not change anything: PYD, through YPG, remains in control of the region and the members of SKNC are marginalized and living in exile in Iraqi Kurdistan. The bridge that connects the Southern and Western Kurdistan has become a tool of political pressure for Erbil to muscle out PYD and to impose a negotiation on other Kurdish parties regarding the distribution of power on the territories that it controls.[/mfn] between the PYD[mfn] Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat – Democratic Union Party. Branch of the PKK in Western Kurdistan (Syria)[/mfn] and the KDP[mfn]Kurdistan Democratic Party of Masoud Barzani.[/mfn] led to the closure of the bridge and the other few kilometers of border that separate the Kurdish autonomous region and Syria. Since then, illegal crossings take place at the south of the Tigris (in the Zummar sub-district), through the disputed areas between Erbil and Baghdad.

Crossing of the Iraqi-Syrian border next to the Simalka bridge

see illustration n°2). The contiguity of villages added to social proximity makes this area an alternative for smuggling when the bridge is closed: support networks are thus mobilized to transfer the refugees willing to reach to Iraqi Kurdistan. Similar smuggling systems exist between Iraqi Kurdistan and Turkey, in areas under the control of the PKK (regions Qani – Massi, of Mergasor). Similarly, at the south of the border between Syria and Iraq Rabia, Arab Shammar and Tai tribes – who live on the border – move freely between countries frequently, enabling circulation and trafficking of goods of any kind.

Taking advantage of the regional borders’s permeability, as well as of their familiarity with smuggling networks, some Syrian Kurdish refugees were able to cross several state borders before finding refuge in Iraq: this new phenomenon is due to the territorialization of Syrian rebels that restrict circulation within the country since 2013. No longer able to circulate inside Syria, many Syrian Kurds from the Afrin region (west of Aleppo) must now adopt new strategies. Surrounded by fighters of Jabhat al-Nosra and ISIL, certain groups of refugees reached Iraq by crossing illegally to Turkey, before returning to Syria (areas under Kurdish control) and leaving it the same way, towards Iraqi Kurdistan. In many border areas, the explosion of illegal cross-border practices, facilitated by the reactivation of smuggling networks, generated a multitude of roads and possible points of passage between the countries. These illegal practices participate to strengthen cross-border trafficking, which is carried by capillary[mfn]That is to say, there are many possible passages on the same border segment.[/mfn] action (Cuisinier-Raynal, 2001), therefore revealing the extreme permeability of borders in times of crisis.

New trans-border territories? (Syrian Kurdistan, Southern Syria, Syrian-Iraqi steppe)

Developments in the Syrian conflict caused the rise of new actors on the territorial margins. As in neighboring Iraq two decades earlier, since 2012, the Syrian Kurds have been taking control over the areas they populate. The PYD and the YPG, the military wing of the movement, hold the military and administrative control of the Kurdish territory—that is to say, a good part of Syrian territory at the border with Turkey. The closure of the latter by Turkey, and that of the Iraqi border – in the sector of Iraqi Kurdistan – by Erbil, as explained above, pushed the YPG to attack the Tell Kutcher border post (Syria) in early November 2013. Since its capture by the Kurds in Syria, before which it had been held by ISIL fighters, this international border post has become their only exit to Iraq, allowing them to avoid the blockade set up by Turkey and Erbil after its quarrel with the PYD. The cessation of supplies and the almost total blockage of the Kurdish Al-Jazira province since September 2013 urged Syrian Kurds to seize control of a border post and to increase their territorial control to the South in order to restore their vital links with the rest of Iraq – the Rabia border post being under the control of Baghdad. In case of a PYD – PDK rapprochement, the border between the two Kurdistan-s could be reopened and both commercial and human activity could return to normal. A new border crossing, unofficial at first and official later on, via the new Simalka Bridge, could then be created as trade becomes sustainable.

Further south, the Syrian army has also withdrawn from the province of Deir ez-Zor, on the Syrian-Iraqi border. Some of the Sunni tribes have joined the opposition against the regime in Damascus. But since 2012, these margins increasingly serve as areas of passage for Iraqi jihadist fighters reinforcing the Syrian largely-Sunni rebellion. Radical Islamists, like those of ISIL, numerous in Anbar (Iraq border region of Syria), can easily cross the border with Syria through many areas, as it is no longer guarded[mfn]During an interview in Iraq in Spring 2012, a resident of Baaj said to the author that the city had become a bridgehead for the Islamist fighters who came from the Iraqi Sunni triangle (Ramadi, Fallujah, Bagdad).[/mfn]. Moreover, even before 2011 and the beginning of the Syrian crisis, this sector lacked a sophisticated surveillance system and could easily be crossed. It is precisely in this region, which runs from the Syrian-Turkish border to the Syrian-Iraqi border, where Jihadists seek to establish an “Islamic emirate”[mfn]See: http://www.lefigaro.fr/international/2013/07/23/01003-20130723ARTFIG00456-en-syrie-les-djihadistes-rejettent-la-democratie.php?cmtpage=0. ‘‘With its Iraqi allies, the jihadist group would in fact have a ‘Caliphate’ on horseback plan for Iraq and Syria’’ http://www.france24.com/fr/20130820-kurdistan-irakien-afflux-refugies-syriens-djihadistes-front-al-nosra[/mfn]. These regions, although considered as margins by the former authoritarian regime, have always been deeply interiorized by local people[mfn]According to Jean-Pierre Renard (2012), this apparent contradiction between transborder movement/mobility and the desire for anchoring a territorial identity imposes an actual reality for (at) the border areas.[/mfn]. Today, they no longer represent remote areas, as they became central to the Syrian Islamist rebellion due to their permeability. In this new dynamics, the border cannot function as a filter (a role it, in fact, never really played); it rather tends to give way to the free movement of fighters, some of whom – the most extremists –aim at a political project that denies the very existence of these post-First World War boundaries created by colonial powers.

Finally, clashes due to the war raging between loyalist troops and rebel militias in the Hauran[mfn]Daraa Province, where the opposition movement against the Syrian regime had begun.[/mfn], which led to the partial withdrawal of Syrian troops from the southern border, reactivated clan and family ties between Syrians and Jordanians. Although the cross-border trade collapsed, condemning the Northern cities of the Jordanian kingdom to economic slump, some Syrian refugees have been relying, from as early as 2011, on family ties, sometimes very ancient, to settle in Jordanian cities. For example, the concentration of Syrians from Homs in the Jordanian city of Mafraq can be explained by clan relations existing between some families, like the Khawaldey. Many clans and tribes are thus settled between the Syrian province of Daraa and the Jordanian provinces of Irbid and Mafraq (the Zobi , the Khatib, the Khabaï). The spatial spreading of Syrian refugees on Jordanian territories partly corresponds to this logic, at least for the early days of the conflict. In addition, the return of tens of thousands of Syrian refugees to Southern Syria since May 2013 creates an interdependence between Northern Jordan, where some families remained, and Southern Syria, a region that is no longer under regime control, despite the impossibility to freely travel between the two countries. Jordan has extended the coverage of cellular networks, which allows relatives to stay in touch on both sides of the border, still closed to civilians. That is how the region of Hauran broke his ties with Damascus, an area of traditional attraction, since the 2011 uprising.

As for now, the only physical links between the two countries are the military activities. The activists that are bonded to the Command of the Southern front – the Regional Directorate of ASL in charge of the management of military operations in Southern Syria – are the only persons allowed to make round-trips between Jordan and Syria. Eventually, the partial socio-economic integration of the Syrian Hauran into Jordan could be an important turning point for the Syrian conflict, unless the Syrian army regains the upper hand in this key sector for the regime in Damascus.

Conclusion

“hot stripes” within areas of tension. This fluidity, facilitated by the weakening of a previously strong state (Iraq and Syria), creates forms of relational spaces and strategies, as well as new complex spatial practices. Illegal crossings, transfers through other countries in order to avoid some borders, incessant coming and going of refugees, activists and fighters are more and more difficult to monitor. The transformations of these border areas gave rise to original socio-spatial constructions such as regained/reactivated circulation areas, new regions of legal or illegal border economy and buffer or temporary refugee zones (for example, those used by Syrian or Iranian refugees). Therefore, the disjointed and voluntarily separated areas, such as the region defined by the Syria-Israel border, tend to become exceptions in a region where it can be assumed that the future will evolve, in large part, around the mutation of border areas, of which the Syrian and Iraqi conflicts have become the matrix.